About the Author

This website represents the culmination of my time at the University of Texas at Austin receiving my Masters in Media Studies.

I first began to take an interest in machine-human interactions and relationships in Dr. Sharon Strover's "Communication, Technology, and Culture" class, where I was first introduced to the digital influencer Lil Miquela. Miquela was the start of my thinking about the ways that we integrate machines and technology into our daily lives. In following this line of enquiry, I found myself contemplating the way that in taking a recuperative stance toward technology, and in looking at our images of machines and tech through a queer lens, can reveal new modes of being in the world. I found myself transfixed by the ways that these creations are frequently the backdrop that allow humans a way to imagine a different world and a different self. More often than not, these imaginings take on a distinctly counter-hegemonic sensibility.

Halfway through “Communication, Technology, and Culture” (Spring 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic forced us into remote online courses. I’m writing this section on the one-year anniversary of the World Health Organization declaring a worldwide pandemic. Since then, I’ve completed the majority of my Masters remotely.

Her and Aural Haptics

The haptic nature of Samantha's voice and how it constitutes a body

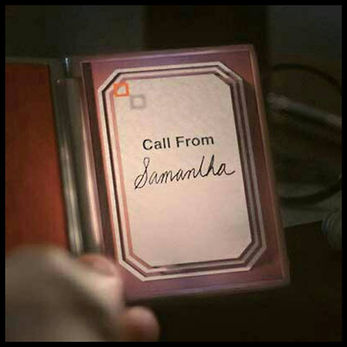

Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her about the relationship between a lonely man, Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), and his AI operating system, Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson), expands upon aspects of Laura Marks’ theory of visual haptics. Marks argues that all haptic images are

erotic because they force the viewer to engage with—and constitute themselves within—the image on screen and not simply just watch it unfold onscreen in front of them. Visual haptics refers to images that elicit a sense of touch within the viewer’s own body, thus obliging the viewer to construct themselves within what’s onscreen. Similarly, Her elicits the same sense of touch and feeling onscreen, except aurally. As the sound of Samantha’s voice transcends the screen and “touches'' the audience by entering their ears, the audience has to construct Samantha. Samantha’s voice performs in much the same manner as haptic images (unconfined by the screen and needing to be constituted by viewers) “touch” the eye. Sound, specifically Samantha’s voice, is even less contained than images on the screen. By adapting Mark’s theories of haptic visuality to the aural qualities of Samantha’s voice Samantha is constructed by the audience in much the same way as one would construct a haptic image in their mind.

Marks' Haptic Visuality

To learn more about haptic visuality, click here.

In her piece, “Video Haptics and Erotics,” Laura Marks remarks upon the means by which “an embodied view is encouraged...by floating images” (2). She calls this engagement of multiple senses through images on screen haptic visuality. In haptic visuality, the “eyes themselves function like organs of touch” (2). Instead of inviting immediate identification with what’s on screen, haptic images encourage “a bodily relationship between the viewer and the image” because the viewer must endeavor to construct the image his or herself (3). Marks also argues that visual haptics is a feminist visual strategy as it applies more to identification with the viewer’s body than it does narrative clarity. By focusing on invoking the viewer’s sense of touch, the viewer doesn’t project themself

onto the figure on screen, instead “resolving [the image] into figureation only gradually if at all” (8). In invoking the audience’s sense of touch from an image, haptic imagery and haptic looking emphasize discerning texture rather than distinguishing form (8). Overall, Marks argues that haptic visuality and haptic looking create a more engaged and embodied viewing experience.

Moving Away from the Physical

Her has a distinct lack of “unstable images.” However, Marks’ framework of visual haptics—built around audiences who are compelled to construct the images and therefore implicating themselves within the mechanisms of desire portrayed on screen—can be adapted to Her. The adaptation of this method is most apparent in respects to the haptic qualities of Samantha’s voice.

The fact that Samantha is only ever featured aurally in Her means that the audience interacts with her differently than the other characters that they can visually perceive on screen. In her piece, ”You bet she can fuck” – Trends in Female AI Narratives within Mainstream Cinema: Ex Machina and Her,” Sennah Yee concentrates on how female AIs are constructed for audience consumption

in the films Ex Machina (2015) and Her (2013). She argues, citing theorist Kaja Silverman, that a disembodied female voice could “disrupt conventional narratives in being freed from the male gaze and its obligations'' (Yee 95). While, ultimately, Yee believes that Her falls short of this possibility as she is voiced by Scarlett Johansson (a popular actress with a recognizable voice) and the film ends when Samantha leaves Theodore. Yee argues this places Theodore at the narrative center and not Samantha. Regardless, I wish to focus more on the qualities of Samantha’s voice and how that entreats the audience within her and Theodore’s relationship, creating a sense of embodiment outside of touch or sight.

From Haptic to Aural

One of the more striking aspects of Her is the aural quality and clarity of Johansson’s voice. Perfectly mixed, Johansson’s voice cuts through each scene endowing it with an unseen presence. While Samantha cannot be perceived visually, there is no ignoring her presence in any scene. A study performed by Juliana Schroeder and Nicholas Epley at the University of Chicago, suggests that it was specifically Johansson’s voice and delivery that made Samantha seem so present. Johansson delivers Samantha’s lines in a “natural voice” condition—meaning that she speaks naturally with paralinguistic cues such as inflection, pitch, and rhythm (Schroeder). A “flat voice” delivery would contain less of these cues and would be more akin to reading a speech written by someone else than it would a conversation.

In doing so, Her prompts the viewers to not only contemplate Samantha and Theodore’s relationship, but to place themselves within it as they construct it. This constitutes more than just “looking” or “watching.” Instead viewers have to create a “bodily relationship” between themselves and the image on screen. The spectator embodies Samantha, while simultaneously acting as a third party watching Theodore and Samantha grow as a couple.

Yee argues that Johansson’s voice detracts from the disembodiment of Samantha as Johansson’s voice is so recognizable that audiences already imagine a distinctly feminine form to accompany Samantha. While I personally disagree, that could be possible for some viewers. Regardless, Johansson’s recognizable rasp and her “natural voice,” not only make Samantha seem human but also inspire a type of aural texture. This texture, in connecting to Marks’ concept of haptics, brings the viewer in to the image. Her voice, and the way that it’s mixed (perfectly clear as though Samantha is in the room with Theodore), allows the viewer to construct, not only Samantha, but themselves in relation to her and Theodore.

To read more about the importance of Samantha's incorporeality, click here.

The BwO and Her |

|---|

Back to Her Entrance Page |